by Benjamin Roberts

I’m sixteen years into my cheese career and I have been fortunate to cross off quite a few destinations off my cheese travel bucket list. I’d been to France, Italy, Switzerland, Spain, and the Netherlands to visit dairies, yet the top spot on my list had eluded me until two weeks ago—the North of England.

One of our longest relationships in artisan cheese has been with Neal’s Yard Dairy in London. For the past 15 years, we’ve bought British farmhouse cheese from their selections. Each week we correspond about what is tasting good and what they think our Minnesota customers (you!) will enjoy.

Of course, I jumped at the opportunity to travel with them on their April “northern run,” a regular trip taken by the team at Neal’s Yard to visit cheesemakers and select the specific batches they’d like to buy. Details were sparse, I only knew that the trip would be packed with visits and that cheese might be our primary source of sustenance.

My Neal’s Yard traveling companions were David, managing partner, Yvonne, sales director, and Bronwen, technical director—some of the most experience people in our industry. Really there might not be a better car to be squished into in all of artisan cheese. Lucky me!

The trip began auspiciously on a foggy London morning at 5am. I was told only to rendezvous at a spot named “7 Dials” and that was it. When the cabby with the cockney accent let me off, I felt like I had been dropped in the middle of a Sherlock Holmes mystery. My traveling companions arrived one after the other and we were off on our way North.

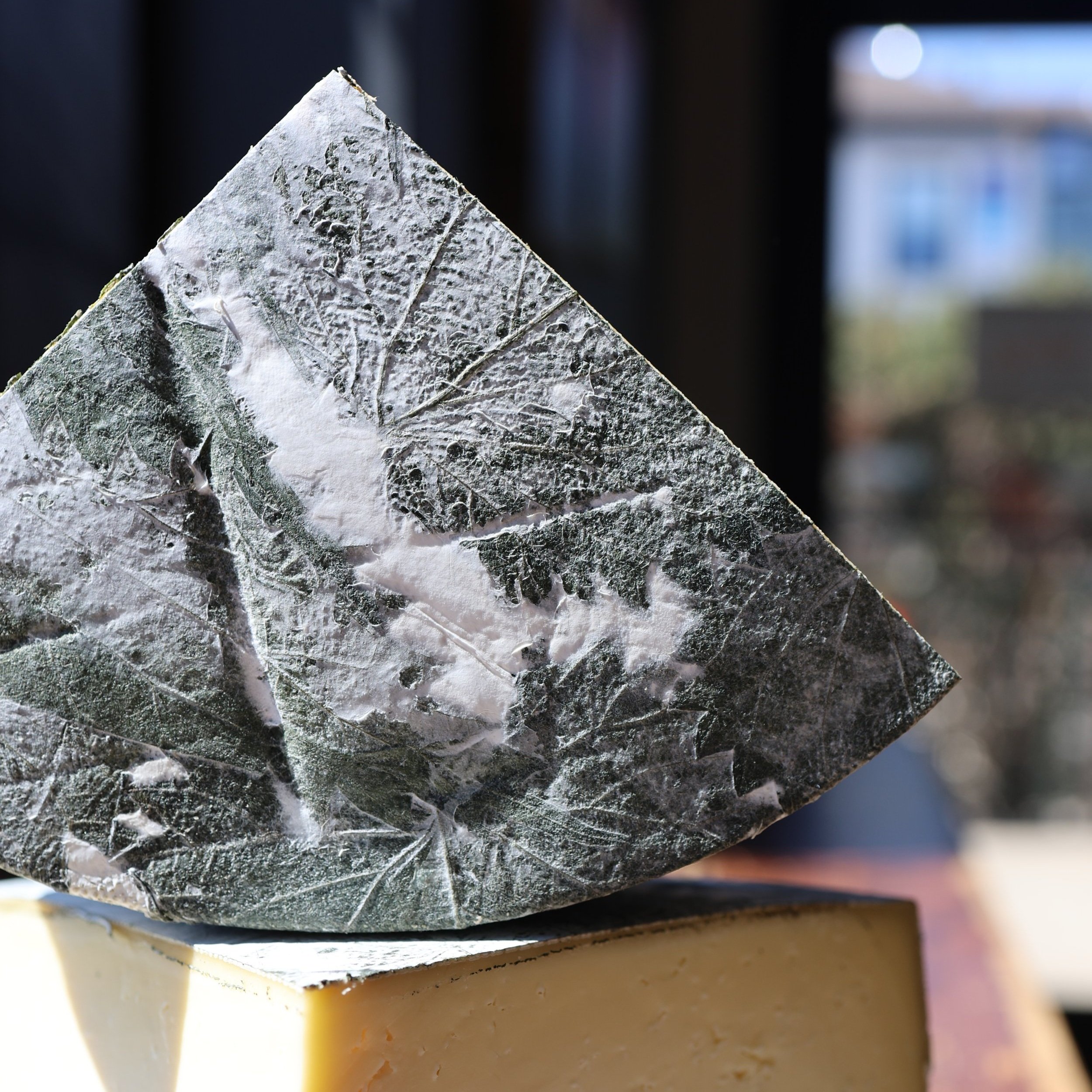

The North of England embraces the capitalized North in the same way Minnesota does. The land is as green as you think it is and the hills even more rolling than you could imagine. Three hours after we had departed, we found ourselves eating poached eggs and toasts in the farmhouse kitchen of the Clark family, makers of Sparkenhoe Red Leicester.

This Northern Run is as much about selecting batches of cheese for Neal’s Yard to sell as it is about checking in on small producers. David visits these dairies nearly monthly and has done so for years and years. These farmers and cheesemakers are their friends and business partners—they depend upon each other for their success. As we ate our eggs, we listened to the tale of an injured cheesemakers (note to self, don’t ride your motorcycle over cattle grates). We heard about the cows that were inside because of soaked fields, and rising input costs.

After catching up, we headed to the maturing room to taste cheese. Shoes off, clean boots on, hair net on, lab coat on, hands scrubbed, hands sanitized. This is a ritual we would repeat countless times on this trip. Sanitation is obviously of paramount importance in these aging facilities.

Batch selection went a little something like this (again this was the routine everywhere we went):

Collected all the batches within a certain time frame. Sometimes this meant trying up to 20 batches in less than 10 minutes.

Cheese iron inserted and a core sample of the cheese was removed for tasting.

Everyone pulled a little piece off the iron, smooshed it in their fingers, and then popped it in their mouths.

Notes were quickly written down along with a grading system

At the end there was a relatively quick discussion about which ones were everyone’s favorites and those batches were set aside.

That’s it! In between some of the batches there was some discussion about acidity or what might have influenced the flavor/texture of that particular batch and what could be done to change things in the future. At some of our visits there was much more discussion of the technicalities of cheesemaking and challenges in the process than at others.

Making a living as a small-scale dairy farmer is difficult no matter where you are, and it is no different for many of the producers we visited. These aren’t passion projects of wealthy landowners, these are young families struggling to feed their families, care for their animals, and make world class cheese—it’s not an easy life.

Over the course of my three days, I ate some spectacular cheeses, and some in search of identity. I heard stories of deep personal struggle, met farmers with wry optimism, and listened to all of the intricacies of managing cheese quality whilst wanting to be supportive of an immense amount of hard work. Oh, and I saw lots and lots and lots of sheep.

Here's my plug for these cheeses: English farmhouse cheeses don’t benefit from subsidies like many other European cheeses. They’re not usually sweet or salty (especially those from the North) and they are often very novel for our American palates. But they’re so worthwhile! Lactic, bright, deeply savory--these cheeses are often the most rewarding on offer in our case.

A few of our favorite cheeses we wouldn’t have in the case without Neal’s Yard: